These two aspects of ourselves were disconnected from each other during the scientific revolution of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries when the rational was favoured and the imaginal was denigrated, giving rise to the severe global ecological, climate and psychological crises we face in our times.

Each hemisphere offers us different views of the world which we combine in many ways: the left hemisphere narrowly focused on isolated lifeless objects, the right empathically connected with the unique individuality of every living being. But this is far too simplistic a model, for, as Iain McGilchrist points out, we need both hemispheres to imagine and to reason.

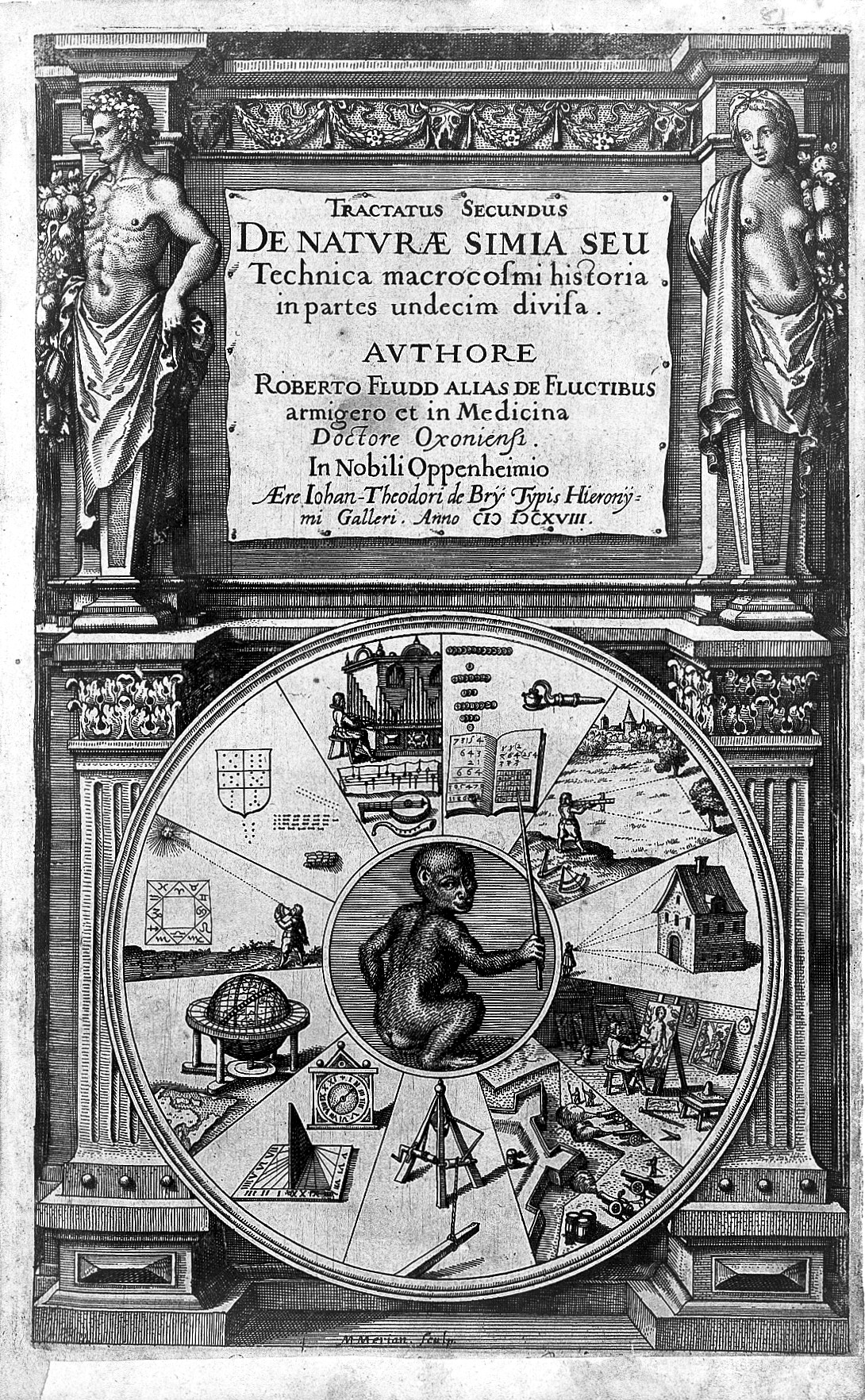

#LIBER PHYSICUS ROBERT FLUDD FULL#

It sees the world with an embodied openness by means of empathy, intuition and feeling and contemplates nature as a series of flowing images full of life and meaning. Our other way of seeing – the imaginal - is mostly associated with our right cerebral hemisphere and couldn’t be more different.

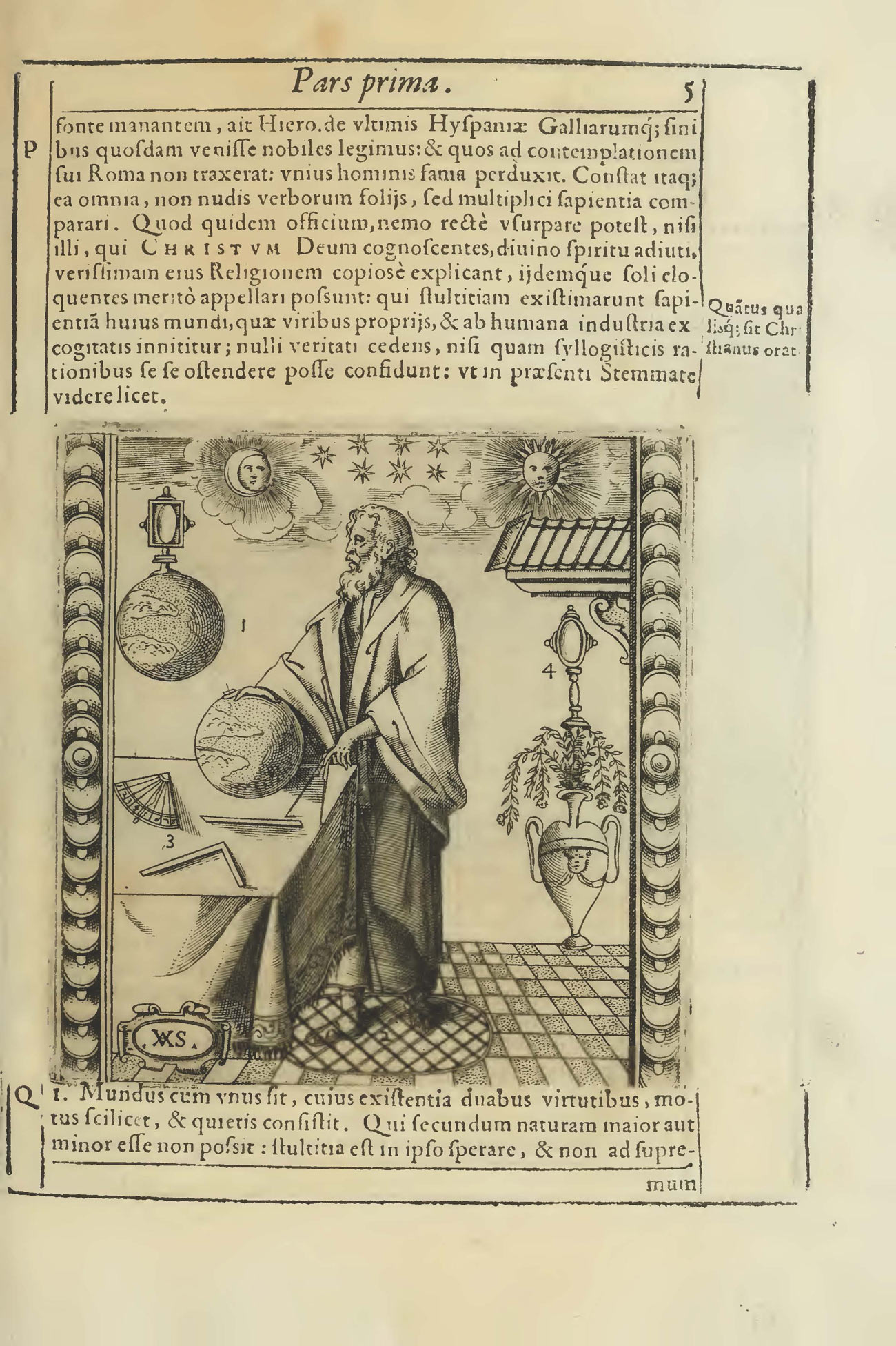

This approach has given us science with all its benefits and pitfalls and tends to immerse us in the experience of being detached observers fundamentally disconnected from a world devoid of meaning and purpose. One, associated largely with our brain’s left hemisphere, is rational and reductionist, operating under the sway of linear logic, cause and effect thinking and sensorial attention to detail. Modern brain science has shown that we humans have two quite distinct ways of understanding our world. But they would resurface in the 20th century in works by a number of outsider, surrealist and modernist artists including Anna Zemankova, Adolf Wölfli, Hilma Af Klint, Ithell Colqhoun, Eileen Agar, and Anni and Josef Albers. With the advent of the ‘Age of Enlightenment’ in the late 17th century and the advance of scientific materialism, many of these ideas were driven underground – hidden for centuries in the arcana of the occult – subject to the same colonial values of ‘reason’ and ‘progress’ that destroyed indigenous cultures abroad. The manuscript was discovered in 1912 and appears to be a pharmacopoeia: an esoteric book of medicine bringing together herbal, cosmological, pharmaceutical and astrological wisdom. These alchemical principles – which were often understood in musical terms – were revealed in the cosmological drawings and illuminated manuscripts of mystics and thinkers like the 12th century German abbess Hildegarde von Bingen, the Jesuit scholar and polymath Athanasius Kircher, and the unknown author of the mysterious Voynich Manuscript – an extraordinary Renaissance codex, written in a still-undeciphered language. Correspondences between movements in the celestial realm and the properties of the material world, the so-called principles of ‘As Above, So Below’, or ‘As Within So Without’, informed a practice of plant-medicine based on the humours of the body. Before the scientific revolution, the medieval European world view was built around these sympathetic and intuitive relationships – a natural science based on intimate, lived knowledge and equivalence and balance with nature.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)